Wendell Berry did not love his elementary and high school education. His best “schooling” days, he later recounted, were his sick days—thanks to the influence and care of his mother, Virginia Berry.

“It was a wonderful thing to be sick and home from school with her, because we would read,” Wendell later recalled in an interview. “We read about King Arthur’s knights and Robin Hood and other wonderful things.”

In school, Wendell made trouble for his teachers and generally did not follow orders. Eventually, his parents would send him to a military school for the duration of his high school years. By the time Wendell began his studies at the University of Kentucky, he admitted he “had not read many books, or many good ones”—but his mind “was furnished with the knowledge of a few good men and good places and good days that had come to me in my life.”1

Wendell went to the University of Lexington with the desire to become a writer, and he was given the gift of good teachers: teachers who challenged his academic carelessness, and shared with him their love for Milton, Dante, and Shakespeare. Indeed, if you begin to look for these three authors in his work, you’ll see them everywhere. But it may be that Wendell has talked most openly about the influence of Shakespeare—and King Lear, specifically—on his work. In his book Life is a Miracle, Berry writes,

“Over the last forty-five years I have returned to King Lear many times.… The whole play is about kindness, both in the usual sense, and in the sense of truth-to-kind, naturalness, or knowing the limits of our specifically human nature. But this issue is dealt with most explicitly in an episode of the subplot, in which the Earl of Gloucester is recalled from the despair so that he may die in his full humanity.”2

This week’s Sabbath poem is all about Gloucester, and so we’ll spend some time reviewing the play before delving into the poem itself.

In the Shakespeare play King Lear, there are two narratives of betrayal and death. First, we have the story of King Lear himself, who rejects the true love of his third daughter, Cordelia, in exchange for the fake flattery of her older sisters, Goneril and Regan. It is a choice that will haunt him to his grave. King Lear, the man whose mind was bent toward hubris and control, goes insane.

But the second set of characters in the play explore a similar theme to a slightly different end. The Earl of Gloucester, friend and counselor to King Lear, has two sons: an illegitimate son, Edmund, and a legitimate son, Edgar. Edmund—like Goneril and Regan—appears kind and loving. Underneath it all, however, he is treacherous and scheming. To gain his father’s title, Edmund convinces Gloucester that Edgar intends to kill him. Edgar must run for his life, and disguise himself as a beggar. After Edgar is out of the way, Edmund persuades Regan and her husband to attack his father. They pluck out Gloucester’s eyes, blinding and banishing him. Gloucester, the man whose eyes were bent toward presumption and control, is now blind. As he puts it himself, “I stumbled when I saw.”3

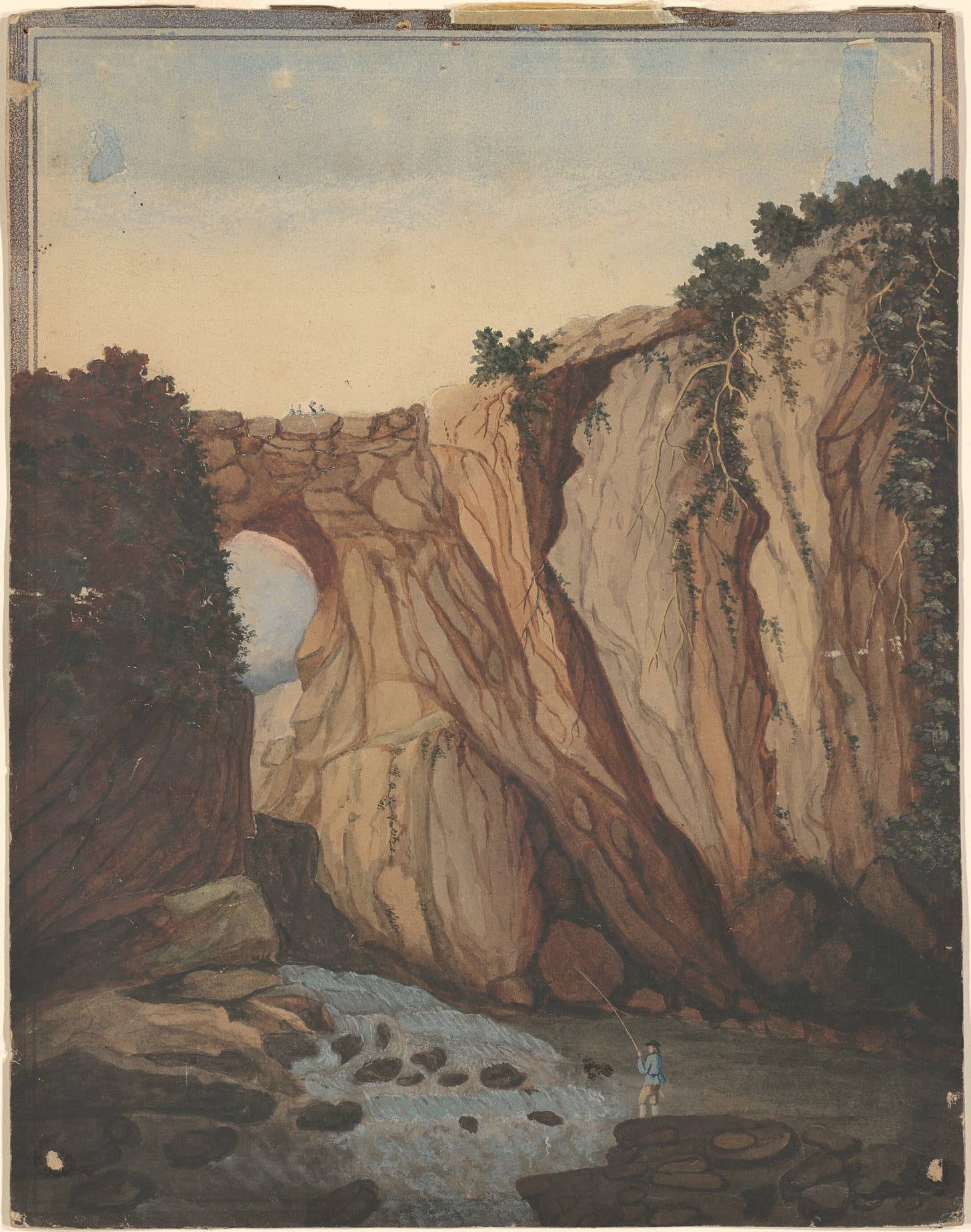

But there is still hope. As Gloucester wanders on the heath, tortured by his choices and loss of sight, eager to die, he is found by his cast-off son. Edgar, still disguised as a beggar, leads and shepherds his blind father along the coast. Gloucester wants to kill himself, but Edgar will not let him. Rather than leading him to the Dover cliffs, where he might jump off and commit suicide (as Gloucester desires), Edgar leads his father to flat ground. He convinces the blind man that this plain is, indeed, a cliff. In vivid detail, he describes a dizzying height to Gloucester: “The crows and choughs that wing the midway air / Show scarce so gross as beetles.”4 Gloucester bids adieu to his companion, and “jumps” from his artificial height. He faints. Edgar then returns to his father, revives him, and declares to him the impossible:

“Ten masts at each make not the altitude

Which thou hast perpendicularly fell.

Thy life’s a miracle. Speak yet again.”5

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Granola to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.