'Live Without Counting'

July 2025 Newsletter: Rejecting chronos for the sake of kairos

Podcasts at 1.5x speed.

21-second Tiktok videos.

In the ticking of the clock, humans find their pace—and their worry. From alarm clock to bus stop to lunch hour. Upon waking, the rush ensues… and almost without acknowledgment, speeds unto sleep.

To be present is perhaps our greatest mystery and challenge. Is it possible to inhabit the flow of time, without thought to what is past or what is coming—to simply be? I would argue that such habitation is vital to our creatureliness (the subject of this summer series). Yet it often feels beyond our grasp.

Wendell Berry confronts the slipperiness of time often. This week’s sabbath poem (from the volume This Day) delves deep into concepts of eternity, presence, and life:

In our consciousness of time

we are doomed to the past.

The future we may dream of

but can know it only after

it has come and gone.

The present too we know

only as the past. When

we say, “This now is

present, the heat, the breeze,

the rippling water,” it is past.

Before we knew it, before

we said “now,” it was gone.

If the only time we live

is the present, and if the present

is immeasurably short (or

long), then by the measure

of the measurers we don’t

exist at all, which seems

improbable, or we are

immortals, living always

in eternity, as from time to time

we hear, but rarely know.

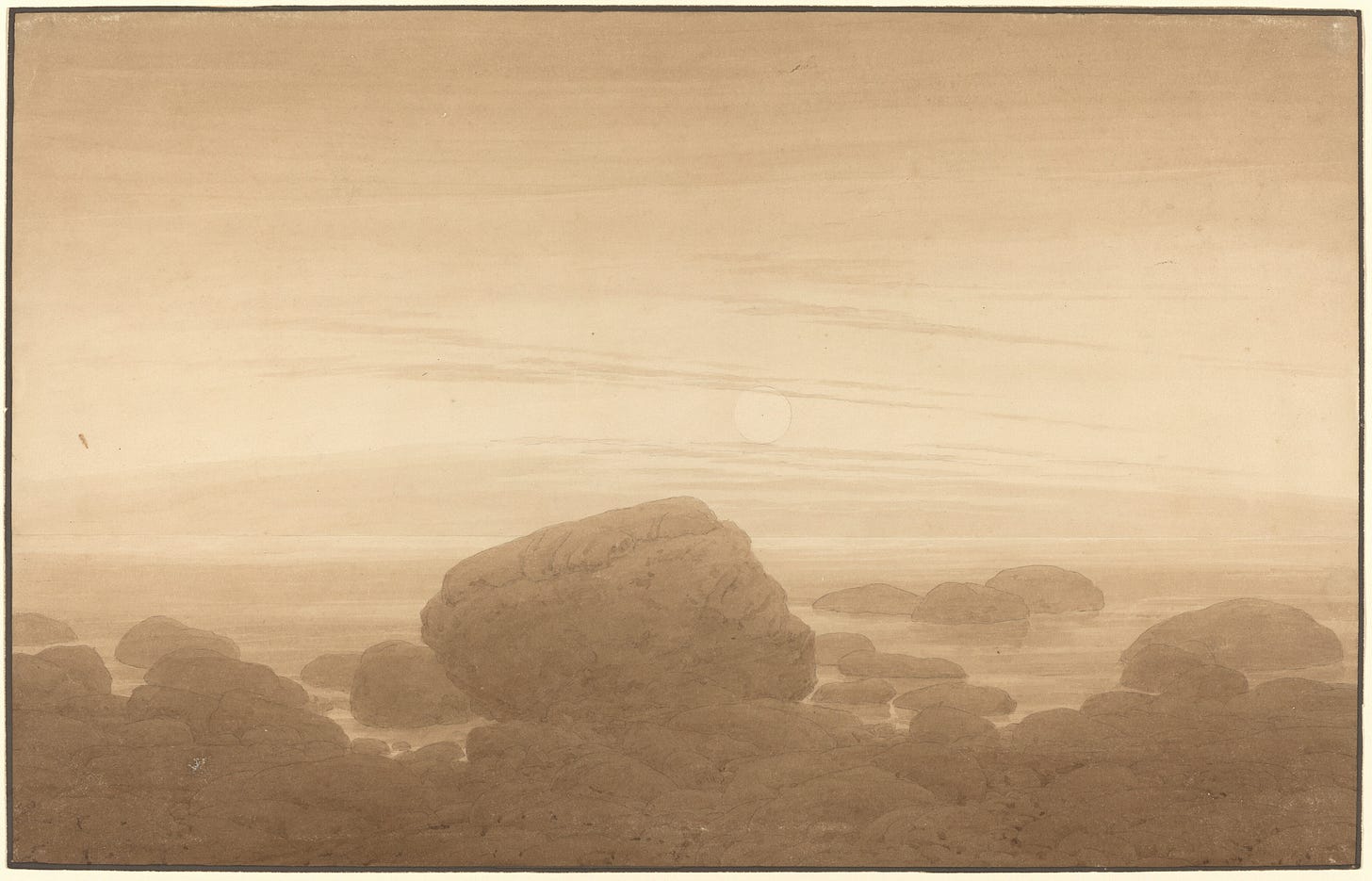

You see the rainbow and the new-leafed

woods bright beneath, you see

the otters playing in the river

or the swallows flying, you see

a belovéd face, mortal

and alive, causing the heart

to sway in the rift between beats

where we live without counting,

where we have forgotten time

and have forgotten ourselves,

where eternity has seized us

as its own. This breaks

open the little circles

of the humanly known and believed,

of the world no longer existing,

letting us live where we are,

as in the deepest sleep also

we are entirely present,

entirely trusting, eternal.

Is it concentration of the mind,

our unresting counting

that leaves us standing

blind in our dust?

In time we are present only

by forgetting time.

The ancient Greeks had two concepts of time: kairos is a qualitative and permanent form of time, one related to the right moment for a certain action or thing. Chronos refers to quantitative or sequential time, what we often think of as past, present, and future: the ticking of the clock.

I love this Berry poem, because its fragmentation, its stops and starts, gives us moments of both kairos and chronos. Indeed, I would suggest that it moves from chronos toward kairos, and shows us how to embrace a similar movement.

We start the poem in chronos, puzzling over time, worrying over the passing of moments. Ironically, these stanzas are the longest in length—yet they feel the most rushed and hurried. Take, for instance, the very first stanza:

In our consciousness of time

we are doomed to the past.

The future we may dream of

but can know it only after

it has come and gone.

The present too we know

only as the past. When

we say, “This now is

present, the heat, the breeze,

the rippling water,” it is past.

Before we knew it, before

we said “now,” it was gone.

Each line breaks here as the present subsides into past: “The future we may dream of” ends, becoming a moment of “only after,” which itself is then “come and gone.” Wendell speaks next of “The present,” but it too falls into “the past.” Unperturbed, he tries again to capture this flow of chronos, declaring, “This now is…” But again the line breaks, before we can declare it “present.” The poet’s every effort to capture a moment, and declare it now, evolves into “past.”

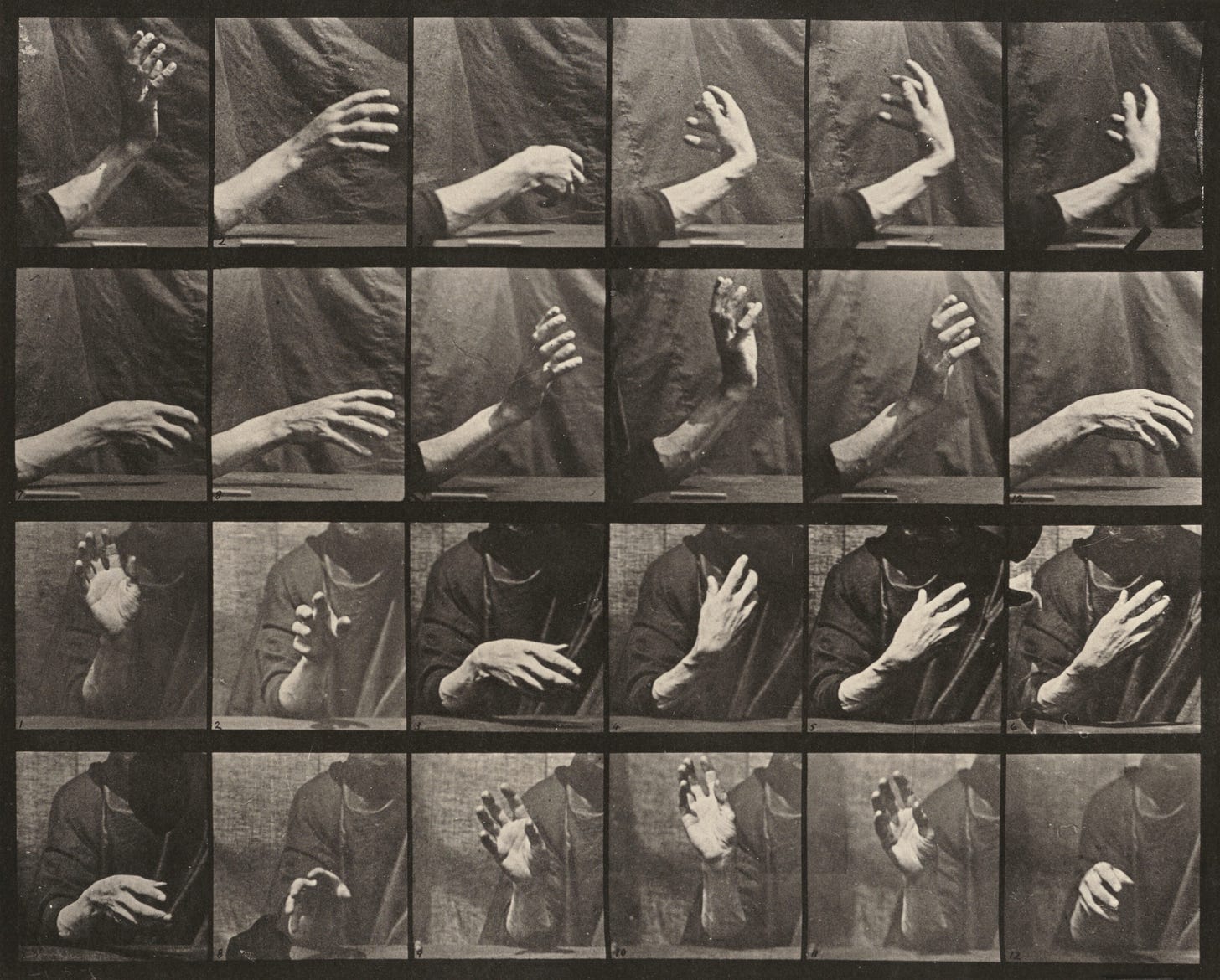

Finally, the stanza ends in a sort of defeat: “Before we knew it, before we said ‘now,’ it was gone.” This is our doom and defeat under chronos. The poet cannot “seize the day.” Time sifts, like sand, through his fingertips, each moment scattering beyond reach.

How do we grapple with this sense of lost time? Wendell surmises in the next stanza that our relationship to chronos leaves us with two possibilities:

If the only time we live

is the present, and if the present

is immeasurably short (or

long), then by the measure

of the measurers we don’t

exist at all, which seems

improbable, or we are

immortals, living always

in eternity, as from time to time

we hear, but rarely know.

“The measure of the measurers” seems to refer to those who wrestle with chronos every day: speeding up their audiobooks, running to the metro, filling their calendars with appointments and meetings, living with the sense of never enough time. The measurers may find, in their reckless futile speed, that life has ceased to “exist at all.”

But this is not reality, Berry assures us. Such a perception would lead us to despair, but it is not in fact real. Our existence is far more probable than the “measure of the measurers.” We just need to see our days anew: to realize that, thought the present may seem “immeasurably short,” we ourselves “are immortals, living always in eternity.”

What does Berry mean by this? I believe this marks the beginning of the poem’s turn from chronos toward kairos: a new experience of being, one set free from the chronological. But I also think he’s hinting at something deep and rich related to life itself—something that inhabits so many of Wendell’s poems, it’s hard to tease it out. I can only do my best. Wendell hints at this idea again in a newer poem, written in 2013:

The old dog with her gray muzzle

and I with my fringe of white hair

please ourselves by nearness to the fire

inside while outside the birds answer

their calling to stay alive. We all

now have fewer days than we had

yesterday. But it comes to me

that I know at last how all of us

are held in the union, the communion, the assembly,

the great membership of this world’s life

that comprehends its numberless

becomings and farewells. In the Kingdom of God

all who ever lived are living.

Only we humans, we the poor,

suffer the ancient mistake, dividing

the living from the dead, confusing life

with time. [bold mine]

As a man who believes in both God and eternity, Berry adheres to the idea that life itself is not truncated by time. Time is a creature, just like us. It is bounded and limited. Life, on the other hand, exists beyond time. It extends outward and upward beyond our comprehension. It recycles, moves, morphs, remembers, and blesses. It is endless. If we live enslaved to chronos, we forget the liveliness we actually inhabit. But it does not cease to exist in its own timelessness.

But how do we avoid confusing life with time? So many human efforts to “seize the day” and live more meaningfully still fall prey to time’s foibles and fears. Bucket lists and New Year’s resolutions keep us focused on the future—conquering the next item—rather than helping us live in the here and now.

In his book of essays The Art of Loading Brush, Wendell elaborates on this idea once more, warning the reader against worrying or obsessing about tomorrow:

“The future is a time and a world not yet in existence…. Because of our love and fear of the future, we have invented several ways of thinking about it or preparing for it.… We want, sometimes desperately, to know what is going to happen…. [But] we give up the incarnate life of our living souls, in the only moment we are alive, in order to live in dreams and nightmares of the future of a world…. Why, living now and only now, should we afflict ourselves with predictions of a hellish future in which we are not alive and perhaps will never live? [emphasis mine.] … By withdrawing our false, speculative, wishful, and fearful claims upon the future, we would significantly and properly reduce the circumstance or context within which we live and think. This would place us within our right definition, our right limits, as earthly creatures and human beings. It is only within those limits that we can think practically, usefully, and so with hope, of our history, of what we have been and who we are, of our sustaining connections and relationships.”

To Wendell, the future is nonexistent. It is an unknown and forever mysterious entity. In an age of weather forecasts, 24/7 news, and AI predictions, perhaps it is easy—all too easy—to forget that. The future does not exist. Only God knows what will happen tomorrow. We do not. To pretend that we could know, if we thought and calculated hard enough, will only result in anxiety. “The incarnate life of our living souls,” meanwhile, must be found in the “only moment we are alive”—in other words, in kairos time.

By “living now and only now,” we can un-learn habits of worry, stress, control, and despair. We can let go of the future, in all its unknown. We can then re-learn, in turn, our creatureliness: the fact that we were never in control to begin with. Time is not life, and life is not time, but somehow found in surrender to both.

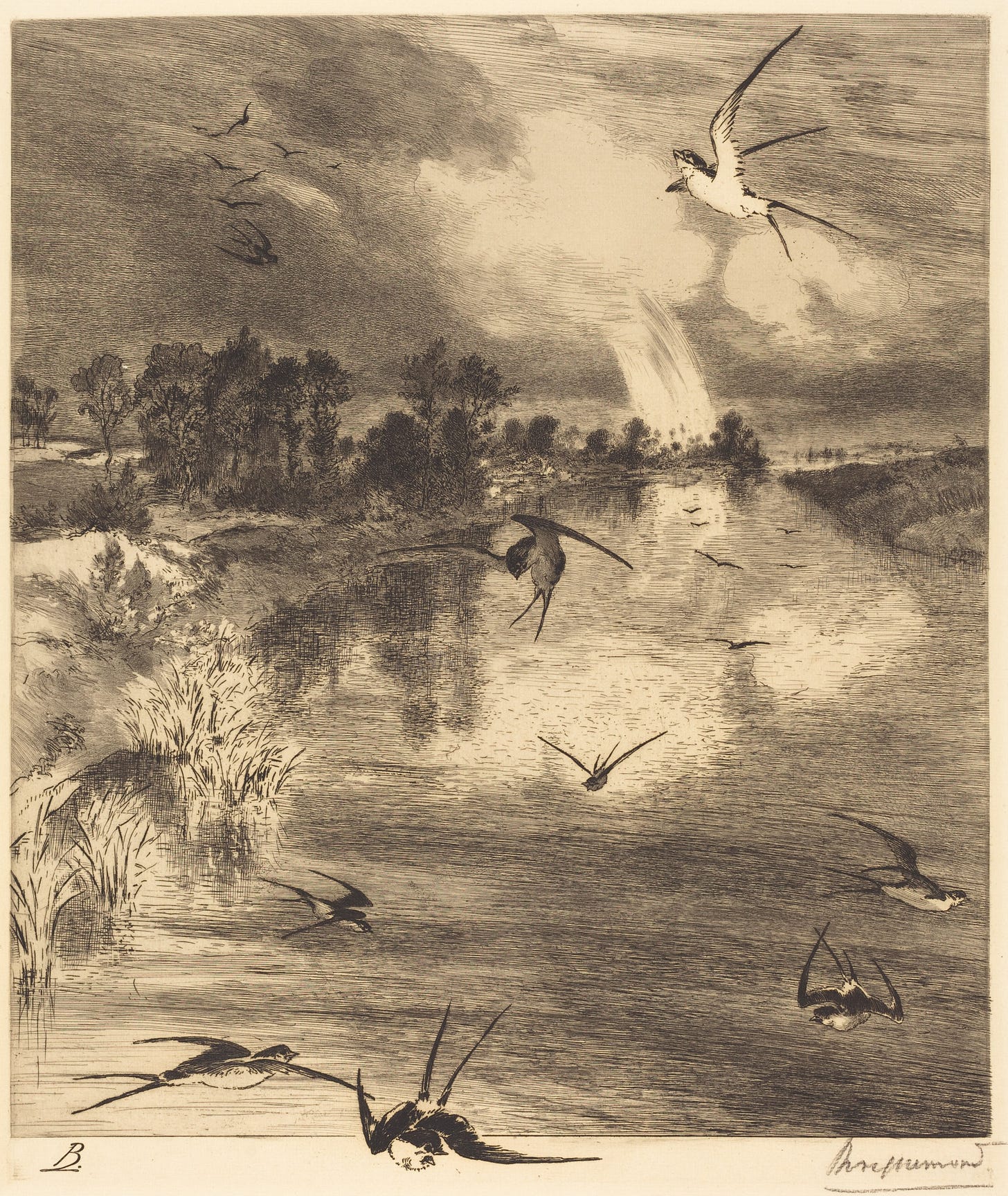

And so the third stanza of Wendell’s poem, even though it is shorter by length of lines, expands outwards in its vision. The poet no longer stresses and worries about time. He is just present. The lines below fill with perceptive verbs and fulsome visions—seeing, sensing, hearing, and feeling what is, in all its imperishable beauty:

You see the rainbow and the new-leafed

woods bright beneath, you see

the otters playing in the river

or the swallows flying, you see

a belovéd face, mortal

and alive, causing the heart

to sway in the rift between beats

where we live without counting,

where we have forgotten time

and have forgotten ourselves,

This is a technicolor, multi-sensory vision: containing the violets, golds, and greens of woods and rainbow, the soft brown fur of the otters, the splash and flow of the shining river, and the flit and scurry of nut-brown swallows against a cerulean sky. Then there is the belovéd, with the accent above the “e” drawing special attention to itself—slowing us down once more, to take in that which is “mortal and alive.” The face might be Wendell’s wife, his daughter or son, a grandchild, or a friend. But in the moment, we know simply the appearance of the face, and in its appearance, the poet’s breathtaking response of love, as the heart “sway[s] in the rift between beats.” To live in kairos is to live in this rift, to “live without counting,” in a forgetfulness that is itself freedom.

Wendell reminds me here of a poignant passage from Jenny Odell’s book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. “Practices of attention and curiosity are inherently open-ended, oriented toward something outside of ourselves,” she writes. “Through attention and curiosity, we can suspend our tendency toward instrumental understanding—seeing things or people one-dimensionally as the products of their functions—and instead sit with the unfathomable fact of their existence, which opens up toward us but can never be fully grasped or known.” Kairos involves a deep attention to what is, so deep that we lose track of chronos and enter another realm.

But in this deep attentiveness, we do not just forget time: we can also learn a quietness of spirit, a self-forgetfulness, that is deeply freeing and true. It is, perhaps, a deepening of love that we find when we plunge into kairos. Madeleine L’Engle agrees with this in her own definition of kairos: “In Kairos we are completely unself-conscious and yet paradoxically far more real than we can ever be when we are constantly checking our watches for chronological time,” she writes. “The saint in contemplation, lost (discovered) to self in the mind of God is in Kairos. The artist at work is in Kairos.… In Kairos we become what we are called to be as human beings, co-creators with God, touching on the wonder of creation.”

And so Wendell’s next stanza, connected to the last, brings us again to that space between heartbeats:

… eternity has seized us

as its own. This breaks

open the little circles

of the humanly known and believed,

of the world no longer existing,

letting us live where we are,

as in the deepest sleep also

we are entirely present,

entirely trusting, eternal.

Rather than seizing the day, here eternity seizes us. As it envelops the poet, something fascinating happens. Two spheres of existence dissipate—one large, the other small. First, the “little circles of the humanly known and believed” dissipate. These suggest bubbles of perception that leave out too much: bubbles in which we scurry about, performing tasks that do not actually matter. In the second line, the “world no longer existing” suggests a surrender of the big picture: worry about the fate of the planet or universe, concerns over climate change, war, famine, and other such perils.

Isn’t it our job to worry over such things, you might ask? It’s a fair question. In the last several weeks, it has been difficult to not tune in constantly to news feeds, to obsess over every new disaster. It has been a time of mourning and pain for so many, myself included. I cannot even begin to list all the woes and griefs of this summer. It is difficult not to stare, without blinking, at the constant horrors of our day.

But obsessive worry does not allow us to “live where we are.” And if we are to inhabit kairos—God’s time—it is vital that we do just that. To live in kairos is to become “entirely present, entirely trusting.” It is not that everything is perfect. Quite the opposite. It is not that we ignore the sadness of the world, either. But the poet who lives in the moment has learned that eternity—not chronos—must reign over both heart and mind.

The last stanza gives us a final vision of surrender. It calls us back to Gloucester once more, to the blindness of hubris and the call of creatureliness.

Is it concentration of the mind,

our unresting counting

that leaves us standing

blind in our dust?

In time we are present only

by forgetting time.

This is the fourth in a summer series on rhythms of sabbath and creatureliness. Other parts are saved for paid subscribers, but you are welcome to join in the conversation here, here, and here!

What is your own relationship to time? Do you feel stuck in chronos? Where (if anywhere) have you experienced kairos?

Is it possible, as Wendell puts it, to “confuse life with time”? How do we get out of this confusion?

What habits or practices, in your opinion, help us to live fully in the present?

The last couple weeks’ “sabbath” adventures:

The kids and I brought vases into the backyard this week, and each worked on our own bouquets. Sweet peas, daisies, roses, dahlias, and zinnias all made their way into the vases. We have loved planting more cut flowers this year (inspired in large part by Tanya Berry).

I have realized that reading aloud in the evenings is one of those rituals that fosters a deep sense of kairos time. We all lose ourselves in it. We have been reading The Vanderbeeker series, The Golden Goblet, and The Hobbit aloud.

On a visit to Virginia last week (ironically, we were not staycationing last week), we went to Harper’s Ferry, and walked along the paths where my husband and I had our engagement pictures taken. It was such a crazy experience of kairos time: inhabiting an old space, an old rhythm, with the new gifts and experiences that life has given! Our kids loved walking along the old canals and across the bridge. They did not, however, love the humidity.

Other wonderful adventures in Virginia: hunting for crawdads, catching (and releasing) fireflies, and eating ice cream in the rain.

We just picked bagfuls of apricots at my parents’ house, and are freezing them for smoothies.

Share your moments of kairos and sabbath in the comments, or via email!

essays and news

Robert Joustra urges us to consider the “geography of ideology”: “Sometimes it is the most difficult to discern the evils, the idolatries, the ideologies that make up the very air we breathe, the atmosphere that gives shape to our communities’ lives.”

Mary Townsend reminds us that freedom is often preserved through the ordinary, annoying modes of communal disagreement and deliberation: “making decisions in an association allows you to remember and practice not only what it’s like to know what you think is best to do, letting someone else decide while you fume in the back row, or trying to beg the favor of someone more powerful as a treat, but practicing the art of argument, persuasion, and often no small amount of begging one’s fellow man, in service of some real if minor practical end.”

Thankful for Matt Miller’s “Seventeen Theses on Writing and Place.”

Lauren Groff argues for Mansfield Park as Jane Austen’s greatest novel.

It’s from November, but I am still thinking about Mike Sacasas’s Substack post on words-as-amulets: “Like an amulet worn around the neck, these words might somehow shield or guide or console or sustain the one who held them close to mind and heart.”

food and drink

Our favorite zucchini bread. Also: zucchini butter pasta.

Don’t let summer pass you by without making Alice Waters’ ratatouille!

Easy, delicious weekday dinner: chicken tinga tostadas.

I could not love this more!

Thank you, your thoughts always expand my own.

Thank you for this! Time--not just "time management" but time itself, and our relation to it--has been much on my mind lately. Perhaps it's because of summer; the stretched-out days evoke some faint sense of eternity. In any event, I've found myself looking back at Augustine's thoughts about time in the Confessions, and also at the Epistle to the Hebrews--especially chapters 3 and 4, where the *chronos* of "today" becomes the *kairos* of an eternal "today," the true Sabbath we should strive to enter (even now!) and in which we rest from our works "as God did from his." Astonishing, this. We need all the help we can get in striving to enter it, and I'm glad to have your essay as one aid.