Finding Margin

Why we plan for the unplanned

“I need to build some margin into my life.”

Or,

“I’m looking for some margin in my schedule.”

I’ve spoken these sentences several times over the past few months. And the word “margin” has settled in my brain like a burr, teasing and tugging at my thoughts.

The definition of margin is far from one-dimensional. It encompasses the borders and edges of things, the way we frame our discursive, financial, and geographic lives. It can refer to the uppermost reaches of success (a sizable profit margin, for example)—or, according to Merriam-Webster, to a “bare minimum below which or an extreme limit beyond which something becomes impossible or is no longer desirable.”

And then there are the times when margin refers to the in-between spaces: it is that spare amount—thick or thin—scattered along the edges of days, votes, budgets, workplaces, and pages. Margin, in this sense, creates a layer of contrast, contemplation, or protection. A bill passes by a “razor-thin margin.” A prudent CEO creates “margin for error.”

Margin envisions a space that exists beyond the planned, the controlled, and the anxious. It’s more than running on empty. It resists the beleaguered and broken rhythms of busy contemporary life. But it’s also enigmatic: we plan for margin, but we don’t always know how much we will get. Those who margin for error, sickness, and the like, for example, are prudentially leaving space for the unknowable.

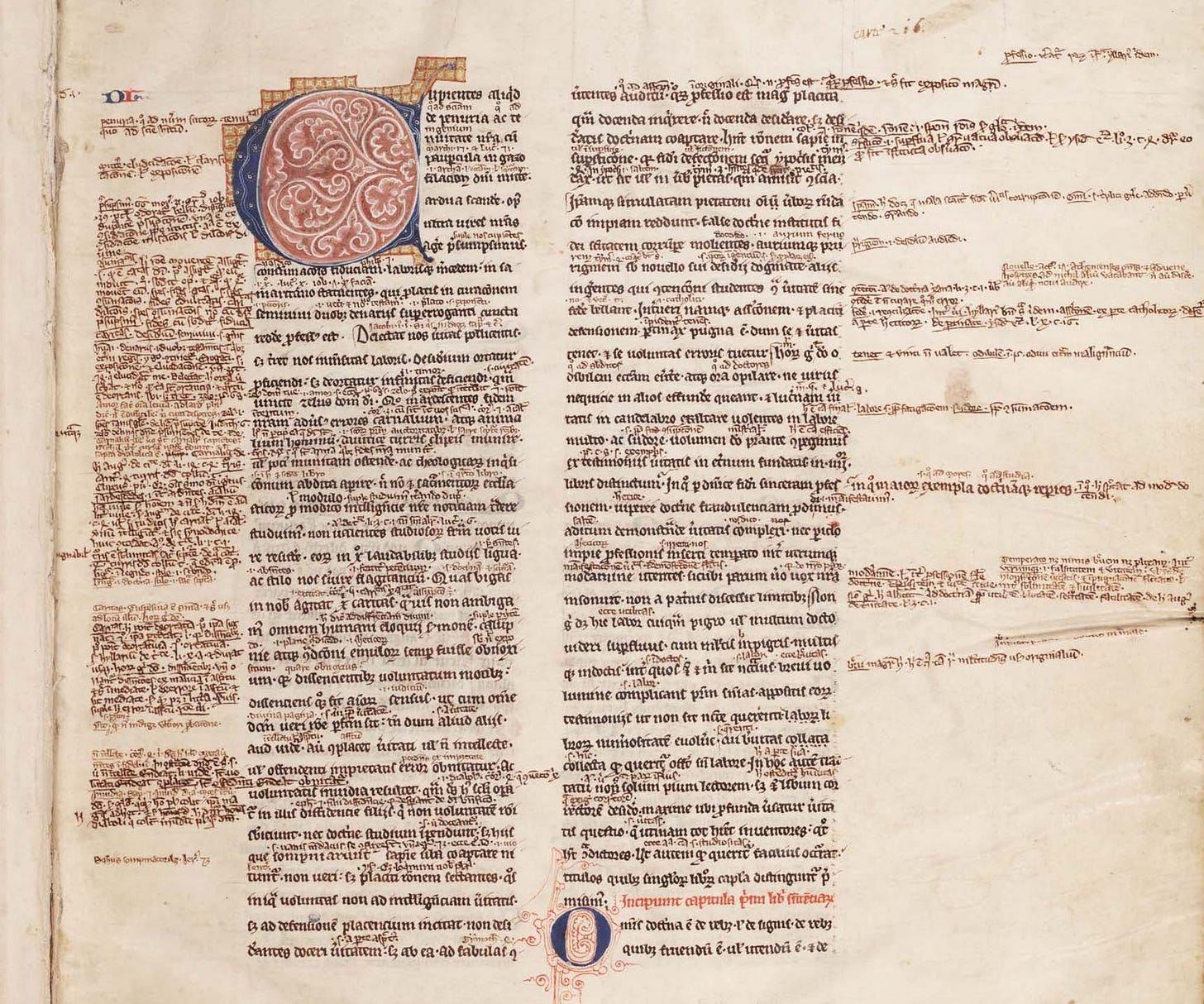

Books, in particular, offer a vision of all that a margin can mean. The blank space along a page’s text is both unplanned and planned: book margins offer deliberate emptiness. They hold space for serendipity and for quiet. Without book margins we would never have marginalia: that delightful catalogue of readerly comments silly and insightful, along with doodles and question marks and exclamation points. But we would also, an article helpfully noted, have nowhere to rest our hands on the page. Margins are a handhold.

What are we holding onto?

To create margin can be a preventive measure. Leah Libresco Sergeant has shared some excellent thoughts on “slack” over at Other Feminisms, and they are very helpful for this consideration of margin. Leah considers what it means (and costs) for a company to build slack into its operations. At one company, for example,

There was cross training on different tasks, so nothing relied on only person. … We spent more time documenting what we were doing, so tasks could be handed off. There was also generous vacation, with a certain minimum required. Everything had to be able to run without you, so it was easier to cover when someone was out unexpectedly.

On Friday, she posted a fascinating observation from an engineer who commented on her earlier post:

I'm an engineer, and in heavy industry most machines and infrastructure are generously overdesigned in order to handle unforeseen stresses. From a bean-counting point of view, this is "wasteful," but it's common practice. It's a shame that workforces can't be put together in the same way, with an intentional "overhire factor" on top of the theoretical bare minimum staff headcount. (We should treat employees at least as well as we treat our machines!)

This is the idea of margin in the negative. It is careful planning for brokenness, loss, or need. But there’s also multiple examples of margin offering us positive space, space for growth, joy, and fruitfulness. Consider, for example, the Year of Jubilee and practice of shmita explained in Leviticus 25. God commanded the Israelites to let their land lie fallow every seventh year. This year of in-betweenness allowed the soil time to repair itself. Perennial plants, wildlife, and even groundwater flourished.

Shmita suggests more than a razor-thin margin, the creation of space and rest just as avoidance of disaster. In an interview with Civil Eats, farmer Lucy Zigward suggested that “what sets Shmita apart from typical crop rotations is that it invites us to re-imagine our fundamental relationship with the land. … Shmita is a full-stop, reset, rethink of cultivation.” The word shalom suggests harmony, flourishing, and wholeness. We see the space of Jubilee as intentional engineering for grace.

And so moments of unplanned, serendipitous flourishing aren’t superfluous: they are necessary. We need to intentionally engineer our lives for grace. We need our own rest days, perhaps even rest years.

Margin, when and where it refers to life planning, thus seems to offer two possibilities: it refers to the simple blank space we need to be, to hold on and rest when life is hard. But margin can also, like the blank space on a book page, invite us to be creative and serendipitous, to laugh and muse and delight. We need both.

Where have you found “margin” in your schedule? Is it a negative or positive concept for you?

Why do you think our world is created with the need for rhythms of shmita vs. relentless productivity? How might we better engineer our workplaces, farms, communities, and homes for grace?

news + essays

Thomas Talhelm suggests that the rhythms of interdependency and cooperation practiced by rice farmers are essential when confronting major crises like the Covid pandemic.

Simple tips to help eliminate food waste.

Boyce Uphold warns that our cheap eggs are dangerous: “Modern egg farms are less agricultural than sci-fi dystopian. The birds are stuffed into cages that offer less than a single page of printer paper’s worth of space; the cages are stacked, row after row, with some facilities housing more than a million birds…. For an influenza virus, such barns are paradise.”

Casey Cep considers the age-old difficulties of distraction, and how medieval monks fought it.

How to tell if your brain needs a break.

Should we make a habit of having more fun?

books

The Four Loves, by CS Lewis

I’ve been re-reading chunks of this book alongside several classic works of fiction—Pride and Prejudice, Kristin Lavransdatter, A Tale of Two Cities—and I’ve realized, through the process, that I never value storage (affection) highly enough. We talk a lot about agape (the highest form of love), eros (passion), and philea (friendship)—but storge doesn’t get enough attention. C.S. Lewis suggests “friends and lovers feel that they were ‘made for one another.’ The especial glory of affection is that it can unite those who most emphatically, even comically, are not; people who, if they had not found themselves put down by fate in the same household or community, would have had nothing to do with each other. If affection grows out of this—of course it often does not—their eyes begin to open. … In my experience it is Affection that … [teaches] us first to notice, then to endure, then to smile at, then to enjoy, and finally to appreciate, the people who ‘happen to be there.’ Made for us? Thank God, no. They are themselves, odder than you could have believed and worth far more than we guessed.”

food + drink

We love these black beans, and make them almost every week.

My children have definitely been raised by millennials, because this is their favorite breakfast treat.

Recipes to try: no-knead seeded honey oat bread, blender chocolate chip banana muffins, and cauliflower chowder.

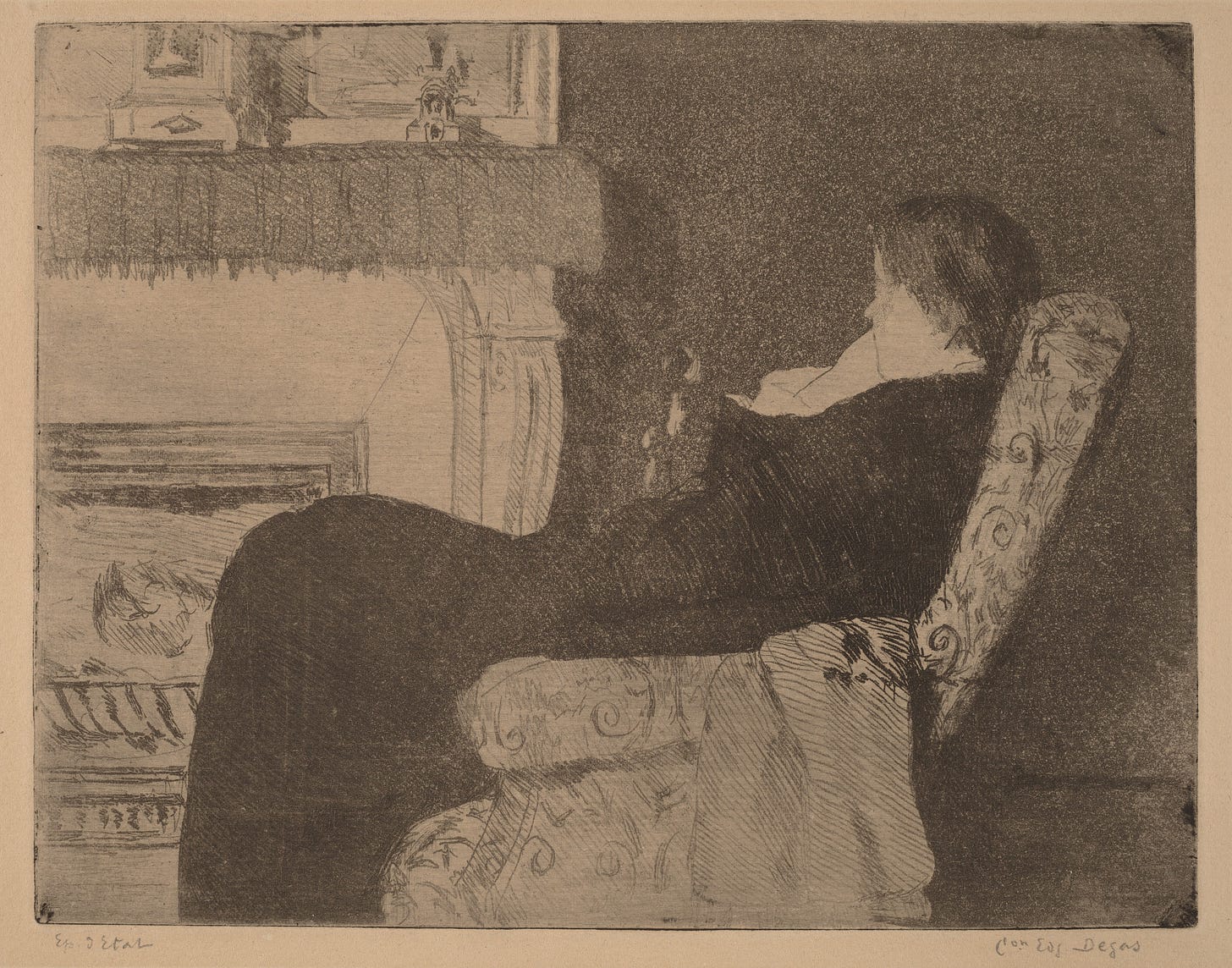

I'm on maternity leave right now, and I've found the times when I'm nursing my son to be wonderful periods of "forced" margin. Even if I have laundry to fold, dishes to wash, and bread to bake, I have to take those moments to sit there quietly with him while he nurses. I've ended up reading a lot more because of it, and I value the quietness of those times—but I do often wonder why I have to be essentially forced into having these margins for reading and for quiet when I know how beneficial they would be even if I didn't have a nursing little one. Why would I otherwise feel so much pressure to be crossing things off of my to-do list at every moment of the day?

Who doesn’t need more margin? Thanks Gracey!