I was rummaging through boxes, looking for old handwritten letters.

It was 2016, and my grandfather had passed away at the age of 90. He was a pharmacist, an artist, and an avid reader. He lived several hours away, and I started writing to him after my grandmother passed away in 2002. For him, that year began a long period of living alone. He dedicated himself to books and paintings, long walks in his neighborhood, and careful care for his garden. When I wrote to him, telling him of my studies and dreams, he suggested courses of artistic or literary study to improve my work. On some letter pages, he would apply flower stickers for me. On others, he drew stick figures to demonstrate an artistic technique.

I finally found the letters in a manila envelope. The yellow notepad paper Grandpa used was covered in spidery writing. As I sorted through them, I realized that this collection of notes only represented about six to eight months of correspondence, out of approximately 14 years of letter-writing. I read through them all, taking in the care and attentiveness each letter conveyed.

Unfortunately, after college and amid a new career and marriage, my letter-writing habit trailed off. I would send my grandfather occasional notes, but never with the consistency with which we’d corresponded in the past. My grandfather was also having more trouble than he used to, but with a better excuse: it was getting harder for him to write legibly, as his hands began to shake more. He would reply to my letters in a firm block print so that I could make out the words.

As I stared at my grandpa’s familiar script, I yearned for a new pen pal—someone who would commit to that faithful, time-intensive habit of letter-writing. Someone who would enjoy resurrecting an old discipline that requires time, attention, and stamps. I wanted something physical that I could stash in an old manila envelope, something that I could read through, laugh, and cry over as the years passed. Something that would last longer than momentary words typed onto a screen.

In the years that passed after that loss, I received a letter from a kind, brilliant young woman I’d met at a conference. Her letters were the start of a beautiful friendship, one I will always treasure. Her letters, like letters from my grandfather, continue to inspire and encourage me.

It’s true that the internet provides ample opportunity (perhaps too much opportunity) to share our thoughts and feelings with others. Perhaps with Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook at our fingertips, we no longer long for letters. We have instantaneous and easy methods of communication available to us. But maybe, as humans drown in an excess of virtual words and messages, at least a few of us long for something deeper and different. Perhaps we still need the kind of intentionality and care that a letter provides.

Edith Schaeffer once suggested that “[w]e all have someone waiting for a letter, and each of us has someone thinking about him or her and wishing the mail would bring some sort of word, some message.” All the words we hold inside, eager to share, “should not be bottled up,” she said. “Start by writing a letter to one person, and continue by writing to others who are waiting for a letter.” What’s more, Schaeffer suggests writing both to friends and relatives and to “strangers”: those we don’t know well enough to feel perfectly at ease with. In these ways, we might encourage new and old friends alike.

I would argue that there are important differences between letter-writing and writing an email or a text. The process of writing a letter requires writers to pause and think out their sentences with greater care. The slowness of writing and transmitting letters builds different mental muscles. It forces focus, patience, and contemplation. And after writers mail their letters, they usually wait days for the response. The degree of patience and care required to maintain this conversation, over miles and weeks of silence, through the process of writing, erasing, and rewriting sentences, can cultivate rich and meaningful communication.

But it’s hard to develop or maintain letter-writing habits when the internet encourages us to abandon them. Which is why I thought it would be fun to host a letter-writing challenge in the month of August.

This month, I’m planning to send paid subscribers thoughts and prompts on a weekly basis, offering ideas as to who you might write to, topics you might write on, and articles/essays on letter-writing as a craft.

Letters don’t have to be handwritten, but I may include some articles/essays on handwriting and cultivating penmanship as a craft/habit.

At the end of the month, we’ll review the processes and habits learned over the course of the month, and think about how we might maintain our letter-writing habits moving forward.

I’m also planning a giveaway for participants at the end of August! I plan to give away 1) a book of author letters, and 2) a stationery set.

To participate, subscribe below:

Letters help us remember the formative moments of our lives. They show us where we’ve been, and remind us of things we should be grateful for. They encourage us to hold fast, stay strong, and keep moving forward.

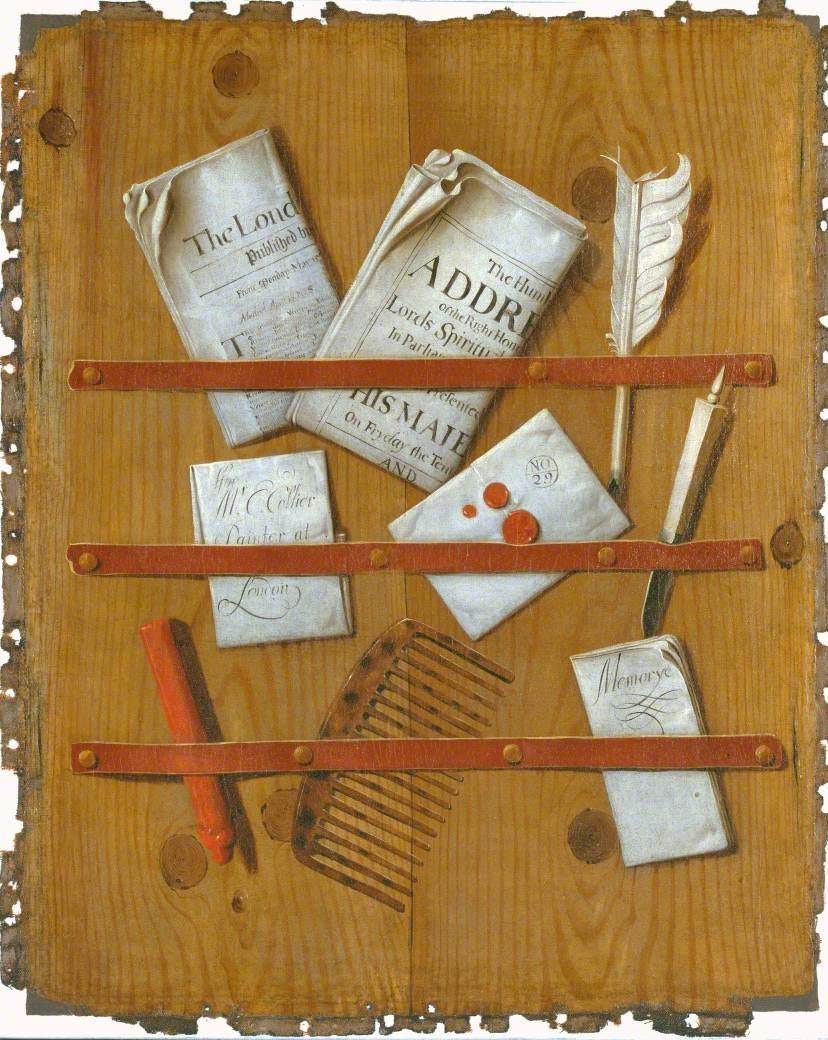

But letter-writing doesn’t just help us to chronicle our own history. In writing letters, we write our histories together. My letters back and forth to my grandfather preserved his thoughts, wisdom, recollections, and jokes. Not only can I go back and get a taste of his humor, insight, and character—I can someday share these things with my daughter, who is too young to remember him. Letters, unlike texts, emails, and Facebook messages, leave a lasting physical archive that we can literally hold onto.

I think most people are waiting for letters, whether they realize it or not. There are few replacements for the intentionality and care exhibited in letter-writing. So hopefully you’ll join me in writing more this month, and in practicing the art of letter-writing together.

Do you write letters? How often? How have you built and maintained the habit of letter-writing?

Do you agree that letter-writing cultivates different habits and qualities of communication? If not, why not?

Share your thoughts and comments via email or in the comments below!

news + essays

Florence Nightingale carefully parsed and visualized data in order to change minds, RJ Andrews writes: “Nightingale packaged her charts in attractive slim folios, integrating diagrams with witty prose. Her charts were accessible and punchy. Instead of building complex arguments that required heavy work from the audience, she focused her narrative lens on specific claims. It was more than data visualization—it was data storytelling.”

Lisa Held warns of the ecological damage caused to agricultural areas through the harvesting of “frac sand”: “While the more immediate impacts of fracking on communities where the drilling itself takes place have been widely covered, silica sand mining has mostly remained in the shadows.”

Matt Bruenig parses recent paid family leave proposals, offering criticism and constructive feedback to policymakers. A great piece for those interested in pro-family policy.

Justin Zorn and Leigh Marz highlight the proliferation of noise in our world, and urge us to seek out silence: “We have to be able to transcend the noise — to withstand and even appreciate naked reality without all the commentary and entertainment and decoration — if we are to perceive what matters.”

“What if … weeds are really here to remind us of the conditions required for creation’s flourishing, or to call us back to our vocation as keepers of creation?” Ragan Sutterfield considers Palmer amaranth and the power of weeds for Plough Magazine.

Ross Douthat critiques the Spotify and Netflix era, in which algorithms hamper creativity and foster homogenous music, fashion, and film worlds: “resisting the rule of the algorithm takes energy and creativity and courage, and the risk for our culture is that our technological skill and our cultural exhaustion are working together, defending decadence and closing off escape.”

Jason Farago considers art in a time of war, and argues, “Somewhere in the interstices between form and meaning, between picture and plotline, between thinking and feeling, art gives us a view of human suffering and human capability that testimonials, or even our own eyes, are not always able to.”

books

The Marginalian offers the poignant true story of the peaceful bull who inspired The Story of Ferdinand—one of the most beloved children’s books of all time.

The Lost Spells, by Robert MacFarlane and Jackie Morris

An absolutely beautiful book of poems, and a delight to read aloud. My daughters and I have loved the illustrations. We also have The Lost Words, and have enjoyed reading it in the past. The Lost Spells is a lovely compliment to The Lost Words, and I would argue that both belong in any child’s library.The Illustrated Emily Dickinson, Ryan G. Van Cleave

I just found this lovely children’s book yesterday, and can’t wait to share it with others. Cleave shares Dickinson’s poems alongside beautiful illustrations, but also includes notes, definitions, and questions on each page for readers to ponder. It’s a lovely way to introduce young readers to the imaginative, complex writings of Dickinson.

food

We may not be in the UK anymore, but I hope to make homemade crumpets at least once or twice a month, and am very excited about this recipe.

I seem to share a new chocolate chip cookie recipe at least once or twice a year… this one is my current favorite. They’re perfectly chewy and soft. I added toasted pecans to our most recent batch.

listening

I recently listened to Rosamund Pike’s wonderful reading of Pride & Prejudice on Audible, and highly recommend it. Now I need to go listen to the entirety of Karen Swallow Prior’s podcast series on Jane Austen, titled “Jane and Jesus.”

I’m nearly finished with Simon Callow’s narration of A Tale of Two Cities, and would also highly recommend it.

Dvořák’s beautiful Cello Concerto in B Minor.

I wrote a letter to a friend recently that I dated 1822 and wrote as if it were 1822.

I write letters infrequently. During the depths of pandemic shutdowns, however, I found that writing letters was a good way to keep in touch with friends. Letters were a tangible reminder of friendship and affection that other virtual forms of interaction could not rival. Letter-writing, as you said, allows for a more thoughtful, slow-paced communication that revealed a side of my pen pals that did not come through even in face-to-face conversation.

During the pandemic there was ample time for sharing thoughts via snail mail. Now that life is mostly back to normal, I'm finding it hard to take that time. A letter-writing challenge sounds like just the thing to restart the habit!