First, thank you to all those who’ve started supporting this newsletter financially. I’m blown away, truly, and cannot thank you enough.

And thank you to all who’ve emailed me, congratulating me on Oxford! I still have some emails to get to, but I haven’t forgotten you, and look forward to responding and talking more in the next few days.

As always, Granola subscribers show themselves to be thoughtful, kind, and immensely generous! Grateful for this community.

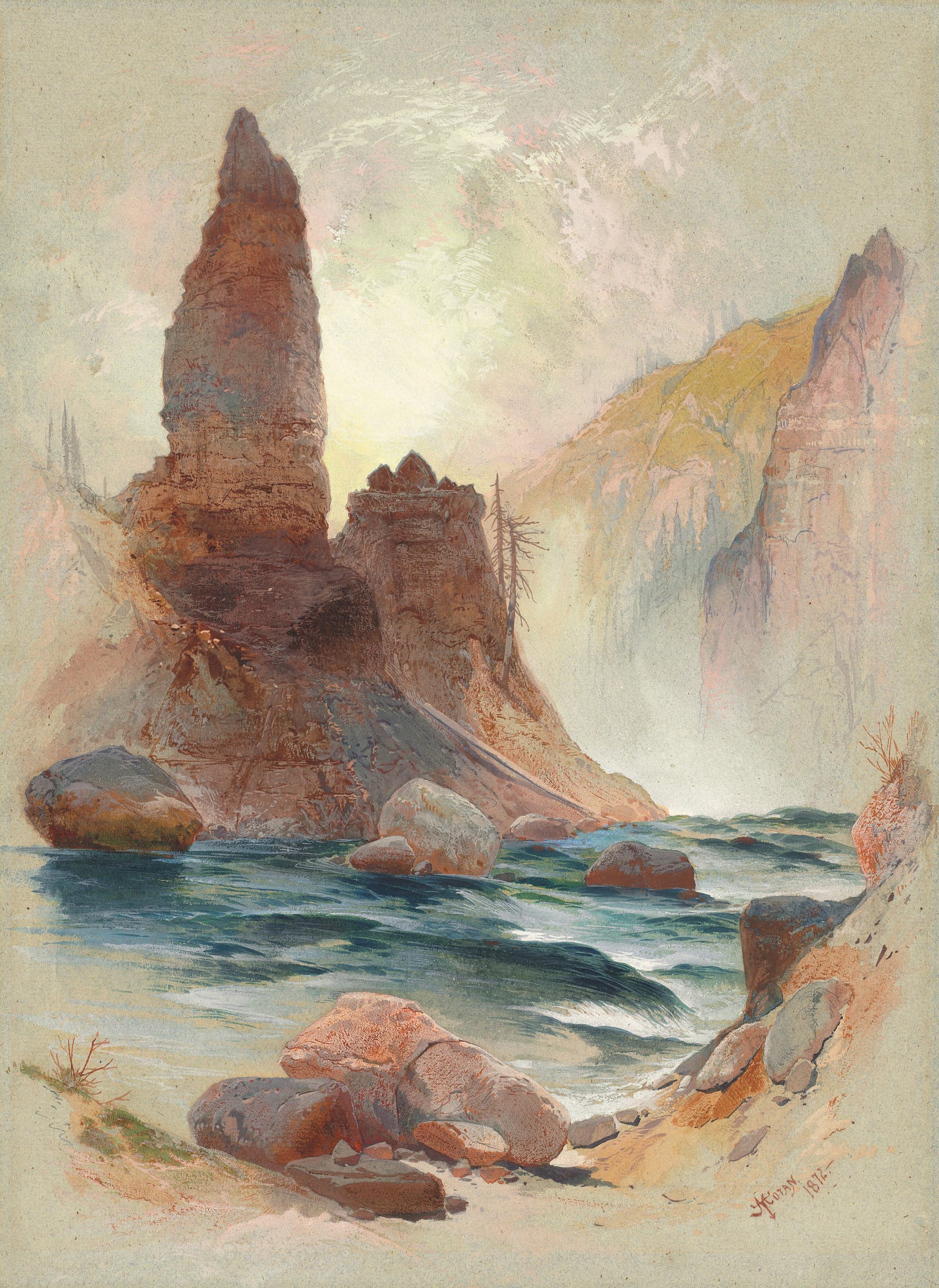

I first visited Yellowstone National Park at age 12. One of my main takeaways at the time, alas, was that sulfur is stinky and greatly impedes one’s appreciation of the gorgeous scenery. But there were a couple awe-filled moments that have stayed with me since.

One was peering into a vibrant blue hot spring (Grand Prismatic Spring, which is deeper than a 10-story building), heated by lava deep beneath my feet. It is a rather terrifying experience if you truly think about it. Your very smallness ceases to matter as you contemplate the fathomlessness, the age, and the otherworldly beauty of the thing in front of you.

Another was being surrounded by a herd of bison, in a tiny little car with my family. It was similarly terrifying and wonderful. Bison are such huge, beautiful creatures. We felt—we were—unimportant and tiny next to them, even in our car. We could do nothing but stay still and stare as they walked around us and peered at (or more likely beyond) us with their lovely eyes.

When my family and I visited Yellowstone National Park a few days ago, however, I kept getting the feeling that both I and the people around me, in our attempts to see and “experience” Yellowstone, were walking through the park blindly.

Walker Percy explains this feeling well in his essay “The Loss of the Creature,” in which he describes our ability (or lack thereof) to truly see the Grand Canyon as modern humans. First, he considers what it would’ve been like to stumble upon it without any knowledge of its existence, hundreds of years ago:

“It can be imagined: One crosses miles of desert, breaks through the mesquite, and there it is at one’s feet. Later the government set the place aside as a national park, hoping to pass along to millions the experience of Cárdenas. … The assumption is that the Grand Canyon is a remarkably interesting and beautiful place and that if it had a certain value P for Cárdenas, the same value P may be transmitted to any number of sightseers…

It is assumed that since the Grand Canyon has the fixed interest value P, tours can be organized for any number of people. A man in Boston decides to spend his vacation at the Grand Canyon. … He and his family take the tour, see the Grand Canyon, and return to Boston. May we say that this man has seen the Grand Canyon? Possibly he has. But it is more likely that what he has done is the one sure way not to see the canyon.

… Seeing the canyon under approved circumstances is seeing the symbolic complex head on. The thing is no longer the thing as it confronted the Spaniard; it is rather that which has already been formulated—by picture postcard, geography book, tourist folders, and the words Grand Canyon.”

I felt this when, during our visit, my family and I sat on a log and watched the Old Faithful geyser erupt. As the plumes of water diminished and finally stopped, a smattering of applause broke out amongst passersby.

I’ve continued thinking about that applause, and what it signifies. Perhaps it was an offering of respect for something beautiful. (Why not cheer for a truly astonishing sight?) But I think it likely was something far different: a designation of the natural world as a show or spectacle for our amusement. We come to Yellowstone (and many other places in this world) as spectators waiting to be entertained, thus turning the sublime into a commodity for our own amusement.

At best, this is silly and foolish—a waste of an opportunity to truly see and love the world as it is. It represents a forgetfulness of our own “creatureliness,” as Norman Wirzba writes in From Nature to Creation : treating the world as something to be manipulated and controlled misrepresents both what our world is (creation), and who we are in that world (creatures).

This perspective (or lack thereof) can even be dangerous. As we entered Yellowstone, a ranger gave us a pamphlet which warned that, while Yellowstone is indeed a great place to photograph wildlife, one should not try to pose one’s children with wild animals. Such a warning would be laughable if one did not detect the tragedy (real or barely avoided) in it. It represents such a huge misunderstanding of the bear-as-bear, or of the bison-as-bison. It shows to what hyperbolic lengths we humans will go in an effort to control, frame, or master our experiences within the world.

In a review of Hertmut Rosa’s book The Uncontrollability of the World, Michael Sacasas suggests that much of modern life is characterized by a desire for control: as Rosa writes, “everything that appears to us must be known, mastered, conquered, made useful.”

“Because we encounter the world in this way,” Sacasas says, “then ‘the experience of feeling alive and of truly encountering the world—that which makes resonance possible—always seems to elude us.’”

I should note that I was not immune to this. Along with everyone else, I was also racing around trying to get the full “experience” (Bison? Check. Moose? Check. Geysers? Check.), documenting it on Instagram all the while. It’s easy to fall into this demeanor without even meaning to.

Percy suggests the primary problem with our modern gaze lies in our dependence on “experts,” who end up mediating the experience for us and prevent us from fully taking ownership of it. “Instead of being a consumer of a prepared experience,” the traveler should become “a sovereign wayfarer, a wanderer in the neighborhood of being who stumbles into the garden.”

But the language of “sovereignty” seems dangerous here. If we think we have any sort of ownership in our wanderings, we are still not encountering the world as it is. If we come to the Grand Canyon or Old Faithful thinking they are “ours” because we’ve received the great privilege of witnessing them, we’ve grossly misunderstood them. We cannot even say that we own our experience of them, as no amount of planning or money can allow us to determine when a geyser erupts, or when (or whether) a grizzly might cross our path. We cannot control the thunderstorms, wildfires, or other surprises that might circumvent or alter our experience. The best we can do is to show up—maybe at the right place, at the right time. To wander in this world of wonders should be a breathtakingly humbling experience: one which reminds us, time and again, how very small we are.

Contrast the control-oriented disposition of seeing the tourist-as-sovereign with Rosa’s vision of “resonance”:

“… What Rosa calls resonance is a way of relating to the world such that we are open to being affected by it, can respond to its ‘call,’ and then both transform and be transformed by it—adaptive transformation as opposed to mere appropriation. ‘The basic mode of vibrant human existence,’ Rosa explains, ‘consists not in exerting control over things but in resonating with them, making them respond to us … and responding to them in turn.’”

In her book How to Do Nothing, which I’ve mentioned in Granola before, Jenny Odell writes of a subversive discipline of being in the world that is difficult, perhaps frustrating, definitely time-consuming—but that helps to re-train our vision and interactions with others. It is the disposition of the bird watcher, who sits and waits for the sheer joy of listening to and observing the bird. It is, or at least can be, the disposition of the gardener, who humbly and quietly tends the soil.

Embracing the world-as-gift means refusing to see things as object, but rather as subject—and ourselves as not having any sort of mastery over them. It’s in that embrace of wonder and creatureliness, one could argue, that we can hopefully find (or begin to find) resonance. We must seek to see the fullness of things that are not-us, not controlled or even fully known by us.

A controlling, commodifying disposition isn’t limited to our interactions in the natural world. In a recent Substack post, Tara Isabella Burton also warned of the ways we can reject resonance in our encounters with other communities and cultures:

“During my time in Tbilisi, I have seen, for example, Georgian ‘hospitality culture’ become its own kind of commodity, with tourists eagerly seeking out invitations to birthday parties or weddings of total strangers on the grounds of having a ‘real cultural experience,’ and Georgians forced—whether through politeness or commercial necessity—to transform that same hospitality into a brand, performing Georgian hospitality at the expense of authentic interaction.”

As I considered my smartphone-impeded gaze in Yellowstone, I thought with horror of how easy it is for parents (myself included) to treat their children this way: to see a child’s experiences, their cuteness, their quirks, through a lens of “shareability” that then turns their fullness and mystery into a commodity we are using for our own gain (like, shares, retweets, popularity, or acclaim). Meanwhile, the phone exists between us and them, impeding (perhaps even destroying) the resonance Rosa speaks of. The phone distances us from the moment and from them-as-themselves.

This is not to condemn the sharing of one’s life on social media; I think that, at its best, sharing images and words and stories is a way to bring a glimmer of beauty into someone else’s day, and to help each other praise what is true, lovely, just, and “of good report.” But it seems, more often than I care to admit, like a dangerous business.

We neither own nor control our interactions in the world. Indeed, as Sacasas notes, “the farther we extend the imperative to control the world, the more the world will fail to resonate, the more it falls silent, leaving us alienated from it, and to the degree that we come to know ourselves through our relation to a responsive other, then also from ourselves.”

But we can humbly seek out something different: proceeding out of the comfortable known into the sublime unknown, willing to be humbled and taught, willing to encounter others—and the world itself—as creatures aware of our creatureliness.

What are some times and ways in which you’ve experienced creatureliness or awe in the natural world (or in interactions with others)?

Do you remember a moment when you were looking at something but not truly seeing it, as Walker Percy describes? How do you think we can fight this tendency?

Is technology usually a problem here, or are there creative ways we can use phones/other forms of technology to help us see and appreciate the world around us? (One that comes to mind is an app I found that helps you identify constellations. My family and I have enjoyed using it, but hope that we will become well-versed in the constellations with time, and won’t have to lean on it for guidance anymore!)

in other news

Two pieces on food insecurity: Helena Bottemiller Evich writes for Politico that monthly child tax credit payments are having a tangible impact on food hardship rates, but Liz Carey notes over at The Daily Yonder that rural food insecurity could increase in coming months.

Leah Libresco Sargeant shared a list of vetted aid organizations for Afghanistan (and comments include aid organizations for earthquake victims in Haiti,) over at Other Feminisms.

Tiffany Owens proffers three important questions to consider while walking, and helps us to see the importance of walking and attending to our places: “Walking for me has become a silent protest against American sprawl. It’s become an embodied expression of my personal commitment to questioning the city.”

The organization WildEast is urging farmers in the UK to sequester carbon through “straight line farming,” thus setting aside corners, edges, and irregular areas of land for rewilding.

Over at Civil Eats, Sarah Mock discusses her new book, Farming and other F Words, and the importance of collaborative farming, or “Big Team farming”: “It doesn’t matter how regeneratively you farm your one acre if your neighbors don’t. The landscape is the landscape, and it sure doesn’t care about your property line. Water flows, air moves, soil blows in the wind, pollen migrates. If the only way to manage in a truly environmentally friendly way is to manage whole landscapes together, that means you have to have a lot of people involved.”

Austin Kleon and Rob Walker discuss curiosity: “curiosity is not a luxury or a bonus or an add-on to life — it’s a vital tool that makes our life and work richer.”

essays

Mountains are often treated as a “commodity to be conquered,” Nick Drainey writes for Inkcap Journal. In the case of Scotland’s Ben Nevis, a race to the summit has led to littering, erosion, and destruction of local flora. “By calming their pace, visitors may learn that there's more to the mountain than the summit, whether that be a mountain hare, rare lichen or the waving of meadow grass in the wind.”

This essay by Jennifer Banks on natality is one of the most beautiful things I’ve read this year. “We have long theological and intellectual traditions that foreground the vanishing, that wrestle with mortality,” she writes. “But our traditions around birth are less reflective. The word ‘natality’ is not widely known, and it has no alternative expression. Hannah Arendt understood birth not only as something we give but also as an experience that is common to us all and that shapes our lives in indelible ways. Birth is a physical event, but we can also think about it. It takes an entire lifetime to learn birth’s lessons, to reflect on its full capacities, to understand what it means to be natal, created, creating creatures.”

Elliott Holt writes of reading the same poem every day for a month: “Revisiting the same poem every day is the antithesis of the attention economy; instead of scrolling along the surface, I’m diving deep beneath it… . But you don’t have to be an artist or writer to benefit from rereading the same poem. I’d like to think that this practice of sustained concentration can also nurture human connection by encouraging the intimacy of attention.”

“By disconnecting science from the broader, systemwide realities of nature, human experience, and emotion, we rob it of its moral power,” Douglas Rushkoff argues. “The problem is not that we aren’t investing enough in scientific research or technological answers to our problems, but that we’re looking to science for answers that ultimately require human moral intervention.”

books

The Last Samurai, by Helen DeWitt

I’ve never read a novel quite like this one. It’s brilliant, and surprisingly funny. The Last Samurai tells the story of a single mother raising a (perhaps) brilliant son, accidentally teaching him multiple languages before the age of five. It’s the story of that boy’s quest to find his real father as he grows older. But the book is also, as Christian Lorentzen notes, an ode to learning: “That art and knowledge, achievement and adventure, are worthy things in and of themselves, not just as a means of attaining capital or worldly status — this is the idea that anchors The Last Samurai and motivates Sibylla’s education of Ludo and his quest to find his true father .… The Last Samurai is, in a few ways, an instruction manual. It contains an ethics of living and learning, but it also attempts to tell its readers how to learn and to show them that they can learn things that they might have thought beyond their grasp.”ICYMI, I got to do a Q&A with James Rebanks about his new book, English Pastoral. We discussed Jane Jacobs and Wendell Berry, regenerative ag and rewilding efforts, and more. Read it here.

food

When your three-year-old brings you a spaghetti squash and says she’d like to eat it, there are all sorts of recipes you can try. But roasting it in the oven, shredding the inside of the squash with a fork and mixing it with a homemade cheese sauce—then re-roasting it until it’s bubbly!—was a fun treat. Said 3yo helped scrape out seeds, shred cooked squash, and mix the sauce. Recipe here.

I’ve made six loaves of Deb Perelman’s ultimate zucchini bread this summer—two with gluten-free flour—and it’s turned out perfectly every time. Easy to make dairy-free, as well.

Ashley Rodriguez shared a genius homemade instant soup idea for camping—or any other occasion—assembled in glass jars: “Miso and broth base rest on the bottom along with a bit of garlic and ginger. Some have dried beef while others have dried wild mushrooms. There’s corn, carrots and scallions and ramen noodles. Copious amounts of hot sauce will be added on the campsite.”

Recipes to try: beet-chickpea cakes with tzatziki, magical basil cream sauce (that doesn’t require cream), creamy white beans with herb oil, and sourdough biscuits.

listening

Have not listened to a lot of podcasts or audiobooks since I finished Moby Dick mid-August. So I thought I’d make a list of things I have been listening to, inspired by Rob Walker’s newsletter “The Art of Noticing” (would love to hear what you’ve been listening to):

Crickets chirping in the evenings.

Hummingbirds flitting about and fighting while we were camping a few weeks ago.

Splashes of toddlers in a creek.

Giggles and late-night cries from my eight-month-old (the poor guy has cut 3 teeth in the last 2 1/2 weeks).

The sound of dishes being washed and stacked.

You can read (and comment on) reactions to August’s newsletter here.

One year ago: Take courage, friend.

Two years ago: What are your favorite September traditions?

I love big thunderstorms! A month or so ago, we turned off all the lights and sat curled up by the window during a huge lightning storm. It makes me think of A Wrinkle in Time, "Wild nights are my glory!"

I'm going to avoid the thoughtful questions and second the praise of the zucchini bread recipe. A newsletter last year included the recipe and I've made it multiple times since. We devour it every time. I gave some to my 11-month-old last week - he also loved it. I'm not much of a cook, but this recipe gave me a lot of confidence that I can do what needs to be done in the kitchen and helps me use the never-ending supply of zucchini.