Taking Care

November 2021 Newsletter

In his book You Are What You Love, James K.A. Smith writes of the modern tendency to see humans as “thinking things,” or, in his words, “brains on a stick”: beings characterized by our thought, but not by our bodies.

If this is true, though, we’re only really living when we are free to think or work without unnecessary material burdens or distractions. Adulthood is a space in which we should be free to exclusively engage in deep thinking, cleverness, and “knowledge work,” as M.M. Townsend wrote in a piece about housework for Hedgehog Review some years ago. This has consequences, however. It means we might become dismissive of various forms of care work, like housekeeping, for instance:

I think our sense of the mindlessness of housekeeping comes about because we see it as that which makes these so-called important life-things recede before the immanence of our daily tasks like eating and sleeping—not to mention the immanent reminder that children and parents present, that we once were very young, and only with luck will be decently old.

My own grumpiness, I suspect, comes from the sense of being half in, half out of the adult world, that I’ve been distracted needlessly from my proper work and proper thoughts. Putting an end to spite and recrimination involves understanding just what it is that I am doing: allowing the world hell-bent on worldliness to world. My hopeless devotion to thought comes to light as something of a tragic flaw. It’s not a coincidence that in our attempt to liberate ourselves from houses and indeed from all bounds, we have become, if less careworn, more anxious and depressed. In depression, we become careless of things, and lose our rapport with them, Heidegger writes; in anxiety, we no longer feel at home in the world. When I recover my respect not simply for domestic work but also for the task of keeping a home, I have taken a step toward ending my homelessness, not as modern, as thinker, or as woman, but as mortal.

An integral part of revaluing stewardship and care lies not just in addressing the utility of such labor (arguing, for instance, that maintenance is vital to public health and wellbeing, or to fighting climate change), or in addressing the cognitive and philosophical goods of the labor itself. We also have to revalue the embodied, immanent aspects of human life—in Townsend’s words, “allowing the world hell-bent on worldliness to world.”

The longer I inhabit life as a parent, the more I see caring for bodies as the most important thing I do. The life-and-death, dire responsibilities of my life are those which have to do with caring for tiny humans: changing diapers, filling hungry stomachs, and bandaging scraped knees. If we structure our economy and culture around ideas that disdain or devalue those forms of labor, seeing them as degrading, or as distractions from “real” work or “real” living, for instance, we incentivize a dangerous apathy toward the needs of society’s most vulnerable humans—as well as toward our own holistic wellbeing.

Valuing embodied, embedded human beings means valuing the work of our hands: seeing our housework, maintenance, and care work as dignified and worth doing, not just as drudgery.

It means valuing others’ care and maintenance: supporting day care workers, construction workers, and house cleaners, and making sure they’re compensated fairly for their work.

And it means valuing the subjects of care: tiny babies, individuals with special needs, or elderly humans, for instance, who are unable to “contribute” to society through work, but whose lives depend on the work of caregiving.

As paid family leave is removed from the U.S. Congress’s discussion of a domestic policy package, I think (and hope) there is still opportunity for us to discuss how we view people and care in the United States, and throughout the world. Do we write or discuss government policy, or business practices, in a way that accounts for the embodied and interdependent nature of human life? When we think about the “good life,” and how it ought to be supported, do we think about isolated individuals living in atomized pockets, or do we imagine embedded, whole, complex lives?

I believe some sort of guaranteed paid family leave policy in the U.S. is long overdue and deeply needed—for reasons I explored in this long book review last year for Mere Orthodoxy. Catholic social teaching convinced me we should see workers as embodied, relational persons first, and support them as such. This essay by Marilynne Robinson, meanwhile, got me thinking some years ago about what it means to see myself as a “citizen,” and not just as a “taxpayer”: as someone with societal and civic obligations, not just a free and isolated individual.

There is room here for you to disagree with me, of course. But I hope that, with intellectual hospitality and humility, we can all consider ways to better support the people in our lives who either need care, or who are responsible for difficult care work. We are not just “brains on a stick.” Neither are our neighbors. So what should we do about it?

Have you discovered opportunities to practice care and/or to support caregivers? What about caring for your own body?

How and where should we avoid the temptation to live like “brains on a stick”?

Email me your thoughts, or comment below!

book club webinar!

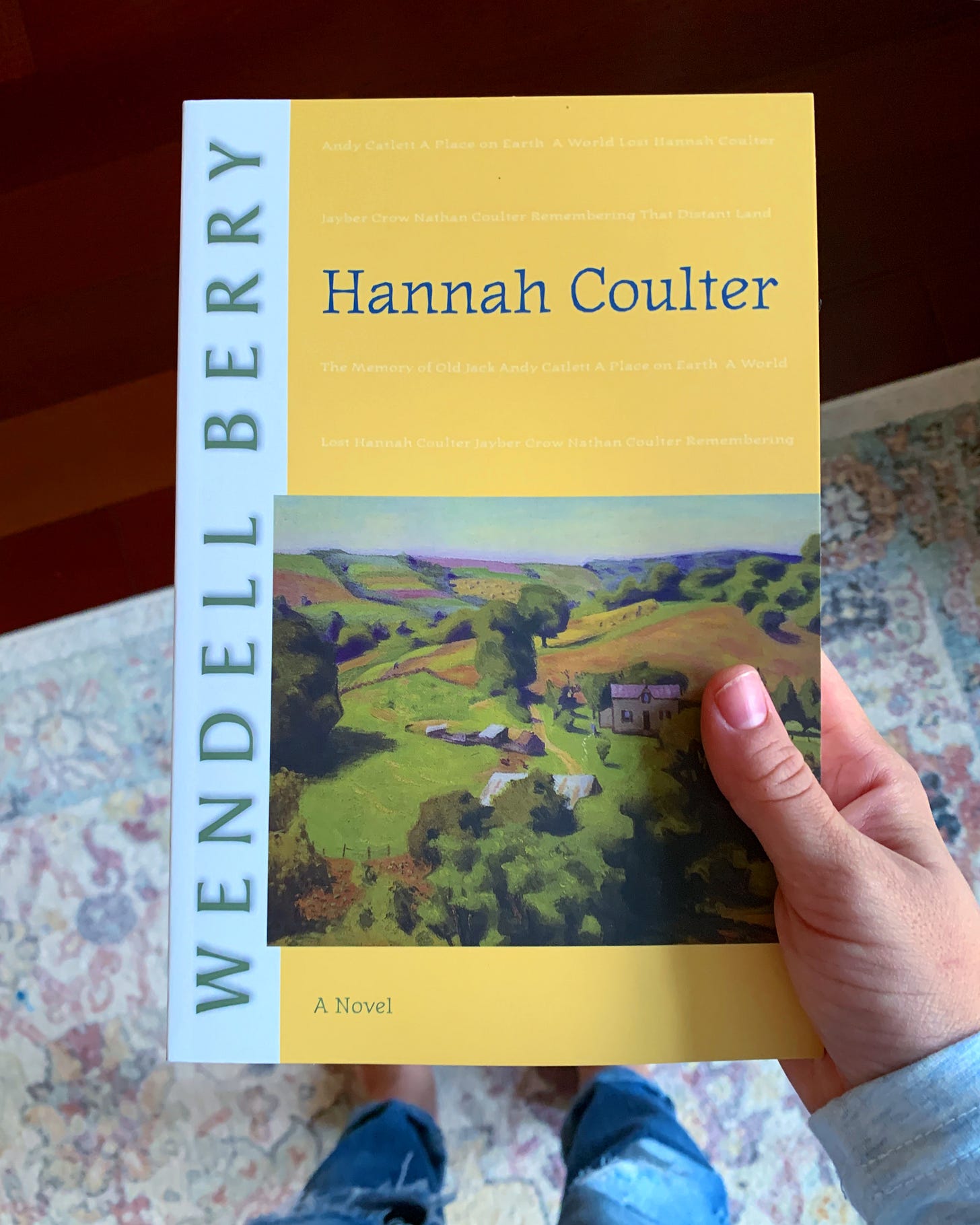

We are starting week 4 of our Hannah Coulter book club this week, and the responses and thoughts have been so wonderful! Thank you to everyone who’s taking part.

It’s not too late to join! If you would like to start reading with us, subscribe here. (**If** you feel a desire to support this newsletter, you can give $2 a month for this subcription, but I offer a 100% off coupon at the link so that you don’t have to.)

Meanwhile, the Zoom webinar—in which we’ll discuss Hannah Coulter with Jeffrey Bilbro, Sarah Clarkson, and Jake Meador—will take place on Monday, November 22nd at 12 p.m. (EST).

Sign up for the webinar here!

in other news

“There’s a healthy debate in both agriculture and climate circles about the value of individual action versus the need for systemic change,” Twilight Greenaway writes for Civil Eats, “And food, thankfully, lies at the intersection of both. What we do—and eat—every day is who we are.”

Fixing problems with the British (and global!) food system requires addressing “agricultural illiteracy,” James Rebanks argues.

What if U.S. Social Security treated caregiving as work? Leah Libresco Sargeant considers the possibilities over at Other Feminisms.

Can hedgelaying survive the 21st century? “Hedgelaying is cold, remote and expensive work – and often goes unappreciated by farmers who have decided that a fence will do the job just as well. It's not an easy career, and simply by creating a bright point in the calendar, hedgelaying competitions are helping the craft, and the craftspeople, to thrive.”

“Instead of opting to order our Christmas presents early, perhaps now is the time to reconsider America’s great shopping addiction,” Terry Nguyen suggests over at Vox. A month ago, a friend on Twitter suggested checking out thrift stores or charity shops for Christmas gifts, and I think it’s a great idea!

essays

Speaking of Amazon—a new book by literary scholar Mark McGurl suggests that Amazon “is the most significant novelty in recent literary history,” transforming “not only how we obtain fiction but how we read and write it—and why.”

“Flowers testify to transience and the impossibility of holding on to beauty for too long, but they are also rugged emblems of resilience and avatars of eternity.”

books

Writing for an Endangered World, Lawrence Buell

I’m reading this one for school, and deeply appreciate the way Buell considers different aspects of embodied existence and ecological concern. He considers the work of John Muir, Jane Addams, Wendell Berry, and Gwendolyn Brooks, among others, and suggests that various urban and rural landscapes can and should be considered together, and loved and stewarded together. “The environmental imagination does not stop short at the edge of the woods.”

Walden, Henry David Thoreau

I just re-read this book, also for school. I found a couple of quotes from an essay by novelist Lauren Groff that helped to describe my first reading of Walden, and my reading this time around. Groff writes,“I remembered the book as an early piece of performance art, an elaborately crafted lie, because while Thoreau was imagining himself rusticated, his mother still did his laundry for him and many nights he showed up at Emerson’s house to eat a far finer supper than the unleavened bread and beans in his cabin that he made so much of in his book.”

But when reencountering the book, Groff says, she found that “this book that first takes the form of a harangue becomes, through each chapter pushing ever deeper into the experience of inhabiting this particular place in time, an exquisite song of praise. … Walden Pond is like all other ponds in that objectively little about it makes this pond stand out from all the rest of New England ponds; and yet under Thoreau’s loving attention, Walden becomes only and miraculously itself.”

food

Made this coffee cake with the girls last weekend, and everybody devoured it.

My husband added shredded beetroot to his potato pancakes a couple weeks ago, and they were delicious! Approximate recipe here. Delicious with sautéed vegetables and a runny egg on top.

Recipes to try: cider-braised chicken and apples, roasted figs, sourdough cider doughnuts, and a buttery mushroom pasta.

listening

The improv principle of “yes, and” helps family members connect with loved ones with dementia, Ira Glass shares on “This American Life.”

One year ago: Why we need gentleness

Two years ago: The consequences of living “debt-free”